Illustration by Research for You

Before we begin this article, please give yourselves a round of applause. Why? Because you are about to embark on a challenging task — reading Chinese.

In many formal and informal rankings, Mandarin Chinese is often listed as one of the most difficult languages to learn. Just the four tones in Mandarin (flat, rising, falling, and falling-rising), homophones, and polyphones make it challenging for foreigners, not to mention the intricate strokes of Chinese characters, which can seem like disobedient alien earthworms to them.

So being able to use Chinese fluently is truly something to be proud of, isn’t it? With Chinese being so difficult, does it not showcase our intelligence compared to foreigners?

Language learning is not a matter of being easy or difficult

It is fortunate that there is no so-called “most difficult language” in the world.

The difficulty of learning a language is relative, depending on its distance from the mother tongue of the learner on the language family tree.

Taking people whose mother tongue is Taiwanese as an example, learning Hakka or Mandarin would be comparatively easier, as they are all Chinese dialects with similar grammatical structures. Take Japanese as another example. As Japanese borrows Chinese characters for its writing systems, native Japanese speakers would learn Chinese characters more quickly than native English speakers.

Furthermore, the learning of a “mother tongue” may not even have issues of “difficulty”.

“Regardless of a baby’s ethnic background, if you expose them to English from a young age, they will speak English; if you raise them hearing Chinese, they will speak Chinese; if they grow up in an African tribe, they will speak a fluent African language,” says Jo-Wang Lin, the Director of the Institute of Linguistics at Academia Sinica.

He adds, “There are between 4,000 to 6,000 languages spoken around the world, so in terms of possibilities, they can acquire any of them.”

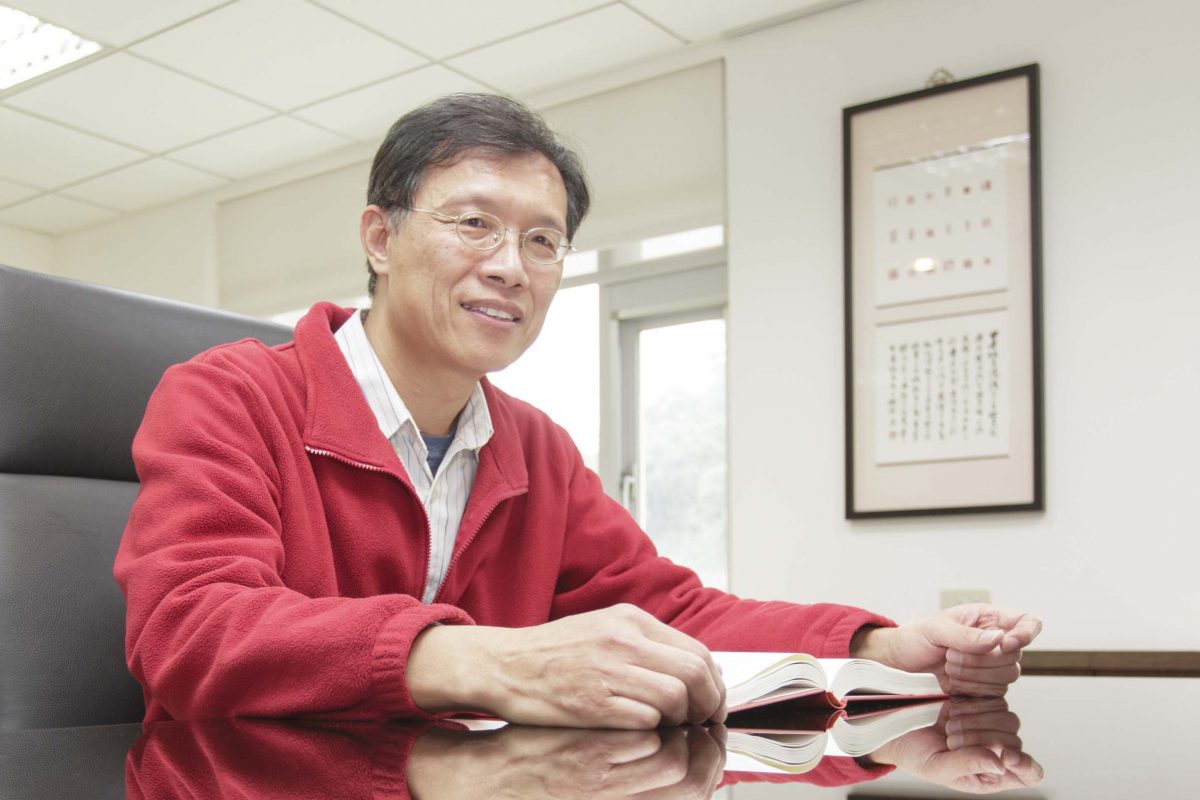

Photo by Research for You

The cognitive abilities of two to three-year-old children are not yet fully developed. Perhaps they can’t tell left from right, or do simple addition and subtraction accurately. However, when it comes to acquiring their mother tongue, they can grow at a remarkable pace. Before the age of four, each one of us has experienced a period as a language prodigy.

The cause of this “miracle”, according to linguistic expert Noam Chomsky, is the infant’s “language instinct”, which is innate, just like sensory abilities such as vision and hearing.

However, such language learning efficiency no longer exists as we grow older. Consequently, when we learn a foreign language, we often encounter many headache-inducing difficulties, such as the hard-to-memorize vocabulary, complicated grammatical usages, or those elusive Spanish rolled r’s.

Jo-Wang Lin believes that while we may not be able to replicate the astonishing language acquisition efficiency of our infancy and early childhood, as long as we can find certain “switches” for language learning, acquiring a foreign language may not be as difficult as it seems.

Reflections in the Mirror: Syntactic Structures in Chinese and English

Jo-Wang Lin begins with the most familiar foreign language for most people: English.

Chinese and English are two entirely different languages. In terms of writing, Chinese employs logographic characters, whereas English uses an alphabetic system. Regarding pronunciation, Chinese is a tonal language, while English is a stress-based language. There are many differences in word order and grammar, too.

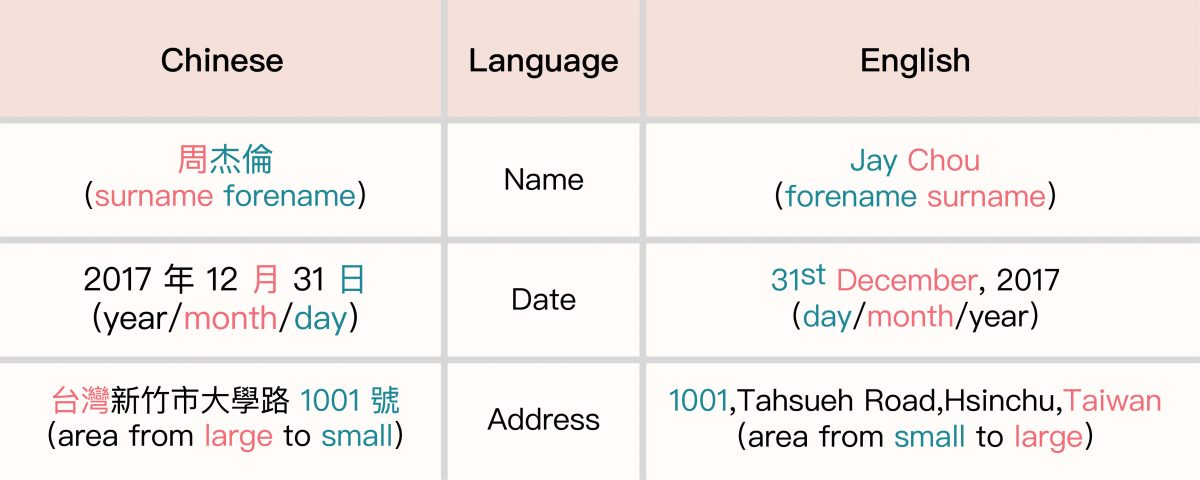

For instance, the order of names is exactly opposite.

In Chinese names, we mention the family name first and then the given name, but in English, it’s the other way around. What’s the reason for this?

When most people are asked this question, the first answer that comes to mind is probably: Chinese value family ties more, so the family surname comes first; Western society puts a stronger emphasis on individualism, hence the reverse order. This explanation may sound plausible, as language does indeed reflect traditional cultural influences.

However, if this reasoning holds, Jo-Wang Lin goes on to ask, what differences exist in the way Chinese and English write “dates” and “addresses”?

Table by Research for You

From the table above, it is clear that not just names are reversed in English and Chinese. The reverse order also applies to the writing of dates and addresses. If the previously mentioned reason of placing a higher value on family ties in Chinese holds true, does it imply that English speakers prioritize “day” or “year”? Do they value house numbers more than the city or country? It seems that the logic of importance cannot be extended to the order of dates and addresses.

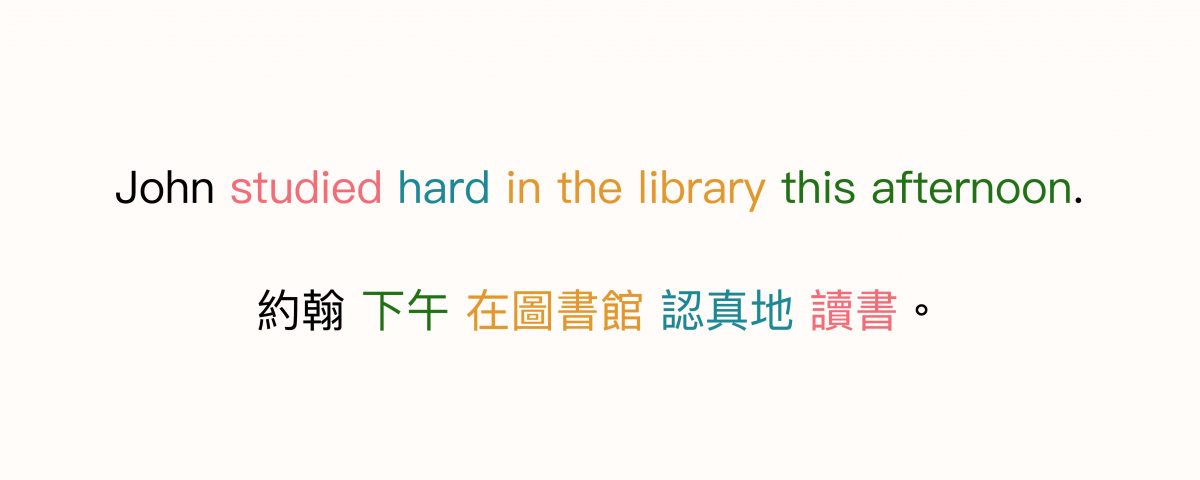

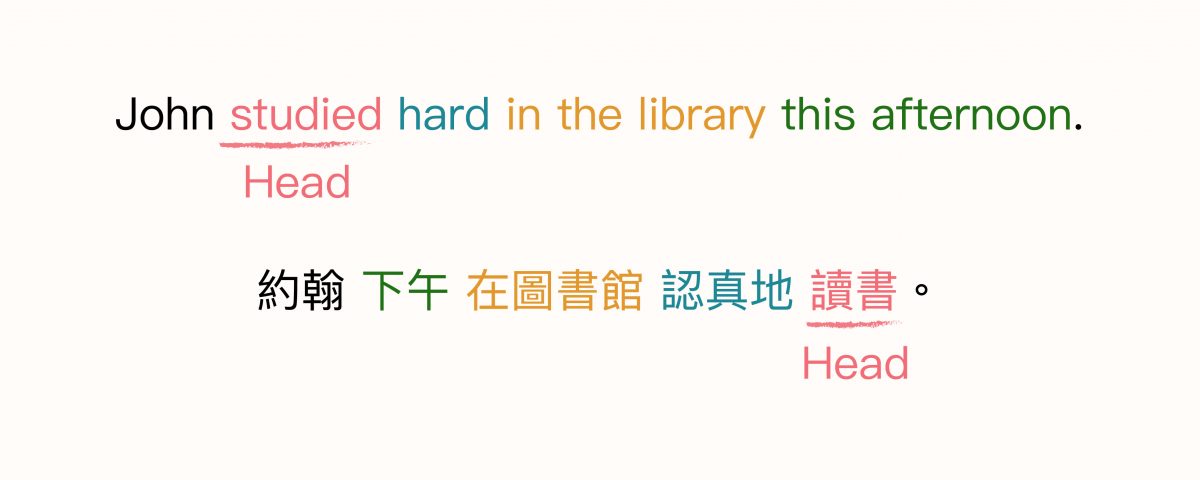

Next, Jo-Wang Lin continues by providing an example sentence.

Image by Research for You

In these two sentences, all the words (phrases) except the subject are in the exact reverse order. After looking at several examples, we can probably discern a pattern. It turns out that although Chinese and English differ greatly, in terms of syntactic structure, they are like two people in a mirror, symmetric to each other.

Jo-Wang Lin continues to use the previous sentence as an example. “Reading / studying” is the central script (verb). “John” is the main character, and everything used to complement the verb are supporting roles (modifiers), forming a verb phrase together with the verb.

Here is the intriguing part: in English sentences, the verb takes the lead at the beginning, with all the supporting roles following. In contrast, in Chinese, it’s the supporting roles that make their entrance first, and the core verb takes the spotlight at the end.

Key to language intuition: head-initial vs. head-final

Image by Research for You

Jo-Wang Lin explains that in linguistics, languages are categorized based on the position of the head relative to its modifiers.

English is a head-initial language, with the head verb coming first and leading the way, followed by additional explanations. In contrast, Chinese is a head-final language. Therefore, in terms of word order, modifiers take the stage first, followed by the core verb.

This fundamental difference between “head-initial” and “head-final” explains the reversed order of names, dates and addresses in Chinese and English.

In terms of names, the surname is just a modifier used to narrow down the scope (e.g. “the Chou family”, while the given name is the central term accurately referring to a specific identity (e.g. “Jay Chou of the Chou family”). The order of names in Chinese and English is determined by the position of the central term.

In Chinese, the central term comes after, hence the order is surname followed by given name. In English, the central term comes first, resulting in the given name followed by the surname. This concept also applies to dates and addresses.

Jo-Wang Lin explains that in the field of generative linguistics, Chinese and English have different “head parameters”. Identifying these parameters in different languages is one of the aspects to which linguists dedicate their research. It’s as if there is a row of switches within a language, and when we grasp a parameter, we activate one of those switches.

Different combinations of these on-off switches result in different languages. So, understanding which switches to turn on or off can significantly enhance the efficiency of language learning.

When most people talk about abstract terms in language learning, like “language intuition”, it’s essentially like this. If you can sort out the rules (or parameters), apply them in various situations, and draw analogies, even languages such as Greek or African languages might not appear so daunting. Put in some extra effort, and maybe you can relive the brilliant moments of your “language prodigy” before the age of four.

Is your research about finding out the language rules to help people learn foreign languages more effectively?

Is your research about finding out the language rules to help people learn foreign languages more effectively?

(Smiling) Actually, it is not quite like that. Discovering these rules is undoubtedly an interesting pursuit, but concerning the parameter of “head position,” it’s actually an important topic within the field of generative syntax in linguistics.

Syntax was my area of interest before my master’s degree, but starting from my doctoral studies, my true research field has been formal semantics or logical semantics.

My research primarily utilizes mathematical and logical tools to explore how language meanings are composed. It involves sets and functions from mathematics to elaborate the combinatory operations of language meanings. In Taiwan, I am considered the first linguist to delve into this area of research, and one of the few in the greater Chinese area.

Why do you like to work on linguistics? Why do you specialize in the area of semantics?

Why do you like to work on linguistics? Why do you specialize in the area of semantics?

My interest in this kind of research developed gradually. When I took linguistics courses in college, I was intrigued by the syntactic structure aspect of language. At that time, what attracted me was the process of discovering language rules and constructing arguments.

Later, while pursuing my master’s degree at National Tsing Hua University, I became fascinated by a “symmetric beauty” in language. I wanted to delve deeper into understanding how this beauty of symmetry was formed. I continued my studies and eventually pursued a doctoral degree in linguistics in the United State.

In reality, it was when I wrote my doctoral dissertation that I began understanding semantics more. During my master’s program, the professors at National Tsing Hua University equipped me with a solid foundation in syntax. So when I went abroad for my doctoral studies, the syntax courses were quite manageable.

However, “logical semantics” was a subject I had never learned before. It involved numerous philosophical, logical, and mathematical concepts, and until just before writing my doctoral thesis, I only had a partial understanding of this field.

But I remembered what my master’s thesis supervisor used to say:

One should have two knives at hand to avoid being caught unprepared in the future.

So I mustered my courage to approach Professor Angelika Kratzer as my advisor, and completed my doctoral thesis while learning and writing simultaneously. This decision officially set me on the path of logical semantics.

The research of linguistics is very fascinating, especially in my research field, where I do not need to rely on any expensive equipment. All I require is my brain, literature sources, and language data bases. I can have an article or a book in my hand anytime, anywhere, allowing me to freely explore the realm of imagination and enjoy the pleasure of research without being constrained by external factors. Therefore, studying this discipline is truly enjoyable.

To be honest, there aren’t really many researchers who work on logical semantics in Taiwan. So, no matter what I do, I often find myself at the forefront. Seeing landscapes that others haven’t explored and making later generations follow in my footsteps, isn’t that also a very satisfying thing?

Photo by Research for You